Little Brown Skink

Scincella lateralis

Common Name: |

Little Brown Skink |

Scientific Name: |

Scincella lateralis |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Scincella is from the Greek word scincus meaning "a kind of lizard". |

Species: |

lateralis is Latin for "of the side", referring to the dark lateral stripes. |

Average Length: |

3 - 5.75 in. (7.5 - 14.6 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

5.3 in. (13.5 cm) |

Record length: |

5.75 in. (14.6 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Scincus lateralis by Thomas Say in 1823, based on a specimen from Cape Girardeau County, Missouri. Mittleman (1950) erected the genus Scincella for this species, but this taxonomy was little followed until it was used in the Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles (Brooks, 1975). Three other names were commonly used for this skink in the Virginia literature. Lygosoma laterale, first published by Dumeril and Bibron (1839), was used by Hay (1902), Conant (1945, 1958), Reed (1957b), Klimkiewicz (1972), Musick (1972), and Delzell (1979). Leiolopisma laterale was used by Dunn (1918), Werler and McCallion (1951), and Conant (1975), who followed Cope (1900) and Harper (1942), although Cope spelled the genus name Liolepisma. Leiolopisma unicolor was used by Dunn (1936), Lynn (1936), Richmond and Goin (1938), Hoffman (1945a), and Carroll (1950), who followed Stejneger (1934) and Stejneger and Barbour (1939, 1943). Scincella laterale, or its emendation lateralis, was used by Burger (1958), Jopson (1972), Brooks (1975), Tobey (1985), and others. No subspecies are recognized.

Description: A small, elfin skink with short, slender limbs reaching a maximum snout vent length (SVL) of 57 mm (2.2 inches) and a total length of 146 mm (5.7 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known SVL is 49 mm (1.9 inches) and maximum total length is 135 mm (5.3 inches). Complete tails were 55.6-67.8% (ave. = 62.4 ± 2.9, n = 42) of total length in the present study.

Scutellation: Body scales smooth, shiny, and overlapping; scale rows around midbody 23-29 (ave. = 26.7 ± 1.3, n = 61); supranasals absent; frontonasal broadly in contact with rostral; supralabials usually 7/7 (95.5%, n = 44) or other combinations of 6-7 (4.5%); transparent patch (window) in center of lower eyelid; mental single; postmental 1; 2-4 pairs of enlarged nuchal scales behind parietals (3 pairs, 77.4%; 2, 4, or combinations of 2-4, 22.6%; n = 62).

Coloration and Pattern: Dorsum tan to golden brown, 6 scale rows wide, and bordered on each side by a narrow dark-brown stripe; dorsal color extends from dorsum of head to distal portion of complete tails; dark stripes originates on snout and passes above eye and onto tail; laterally, body and tail base lightly mottled with dark peppering on a light ashen background; lateral color fades into ventral color, except in some juveniles on which change is abrupt; venter pale cream to light gray; chin and pelvic regions lighter than rest of venter; color and pattern of dorsum and venter extend onto head and complete tails; regenerated tails light brown.

Sexual Dimorphism: Adult females averaged larger (43.1 ± 4.4 mm SVL, 32-49, n = 58) than adult males (ave. = 38.1 ± 4.0 mm SVL, 31-46, n = 49). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.13. Females were also larger in total length (81-135 mm, ave. = 110.1 ± 13.1, n = 18) than males (82-122 mm, ave. = 98.9 ± 11.7, n = 17). Complete tail length relative to total length was similar in both sexes (males 56.5-67.8%, ave. = 63.7 ± 2.8, n = 17; females 55.6-64.8%, ave. = 61.7 ± 2.7, n = 18). Head width in adult males (3.8-5.5 mm, ave. = 4.7 ± 0.5, n = 43) was similar to that in adult females (4.0-5.8 mm, ave. = 4.9 ± 0.4, n = 53), but analysis of covariance revealed that males had slightly larger heads on average than females of the same SVL (J. C. Mitchell, unpublished). There are no sexual differences in color or pattern. The number of midbody scale rows was similar between sexes (males 23-29, ave. = 26.6 ± 1.4, n = 30; females 25-29, ave. = 27.0 ± 1.2, n = 28).

Juveniles: At hatching, the dorsum of the head, body, and tail are bronze with tiny black flecks. The flecks are more abundant toward the tip of the tail. The narrow, dark stripes are distinct on the head, body, and tail but become broken and confused with other markings toward the tail tip. The venter is grayish white to the naked eye, but under the microscope golden flecks are visible. Average SVL at hatching was 17.5 ± 1.2 mm SVL (13-19, n = 21), total length was 38.9 ± 3.4 mm (27-42, n = 16), and average mass was 0.13 g for hatchlings in a single litter.

Confusing Species: Other skinks possess 4 (P. anthracinus) or 5 (all others) light stripes on a brown background, and those in the size range of S. lateralis have blue tails. In P. anthracinus, the frontonasal is separated from the rostral by a pair of supranasals, and dorsolateral stripes are light in color. No other Virginia lizard has the transparent window in each eyelid.

Geographic Variation: No geographic variation in color, pattern, or scutellation is discernible in the Virginia samples. Variation throughout the range of this skink has not been studied.

Biology: This small, terrestrial skink inhabits the leaf litter of hardwood and mixed-hardwood forests. It has been recorded in most forest types where a leaf litter-humus layer accumulates on the ground. Populations may also be found in some urban woodlots; in grasslands that have a thick base layer, such as that found on some of the barrier islands; and in some pine forests. Its preferred microhabitat is the spaces in and under layers of leaves and under the protection of grass cover. The primary activity season is March through October, but S. lateralis has been found active on warm days in all months of the year. Overwintering occurs beneath the leaf layer, and emergence is accompanied by basking on top of the leaves and grasses.

Little Brown Skinks are predators of small, terrestrial invertebrate prey. Specimens from Virginia contained wood-boring beetles, wood roaches, ants, leafhoppers, lepidopteran larvae, unidentified spiders, and isopods. The following prey types have been identified in studies in Georgia (Hamilton and Pollack, 1961) and Florida (Brooks, 1964b): beetles, flies, roaches, crickets, true bugs, springtails, lepidopteran larvae and adults, ants, termites, neuropteran larvae, earwigs, scorpion-flies, fleas, spiders, mites, isopods, land snails, millipedes, and centipedes. Most prey species, such as terrestrial spiders, are those that live in the same microhabitat as the Little Brown Skink. Active foraging (poking the lizard's snout in and under leaves and litter) is used to search out prey. The skink's predatory response is elicited by prey movement (Brooks, 1964b; Nicoletto, 1985b). Predators of these skinks usually live on the forest floor or actively forage there. The only confirmed predators in Virginia are Ring-necked Snakes (Diadophis punctatus) and domestic cats (Mitchell and Beck, 1992). Some ground-foraging birds, like wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), undoubtedly consume these lizards, as well as other predators, such as wolf spiders.

Little Brown Skinks seek escape from predators by running and hiding under ground cover. They are usually heard before they are seen as they run across the leaves. Natural predators are distracted from the body by the motion of the tail, even though the tail is not brightly colored as in Plestiodon juveniles. The ability of S. lateralis to autotomize its tail is an important part of its predator escape strategy. I observed a domestic cat attempt to catch an adult S. lateralis in Henrico County, but the cat was distracted by the thrashing of the autotomized tail while the skink escaped. Tailless skinks from Texas were caught and eaten more often by snake and feral cat predators than skinks with intact tails (Dial and Fitzpatrick, 1983,1984). However, loss of the tail, which contains usable energy (Dial and Fitzpatrick, 1983), affects the lizard's ability to perform courtship behaviors, produce eggs, and escape a later predation event.

Reproduction in female S. lateralis is characterized by small clutches (1-7 eggs each), advanced embryonic development at oviposition, and multiple clutches in the same year (Fitch, 1970). Unlike lizards in the genera Plestiodon and Ophisaurus, female Little Brown Skinks do not remain with their eggs after laying. Mating dates are unknown. In Virginia, the smallest mature female I measured was 32 mm SVL and the smallest male was 31 mm SVL. Females with eggs in their oviducts have been found between 11 April and 24 June. Clutch size was 2-4 eggs (ave. = 3.2 ± 0.8, n = 29). Eggs were deposited in decaying logs and stumps. Two communal nesting sites have been found in Virginia, one with 9 eggs and another with 66 eggs (C. A. Pague, pers. comm.). Average egg size was 10.5 ± 1.1 x 7.2 ± 1.3 mm (length 8.8-12.8, width 5.7-9.0; n = 55). Known hatching dates are 3-4 and 30 July, and 12 August. Oviposition dates and incubation times are unknown.

The population ecology of this skink has been studied in Louisiana (Turner, 1960) and Florida (Brooks, 1967). In Florida, home-range size was 2.5-54.3 m2 for females and 25.1-106.2 m2 for males, and population density was 0.04-0.07 individual per m2, depending on the month of the year. Population density in Louisiana was 0.15 per m2. Brooks (1967) determined that half or more of the lizards in his population did not survive more than 1 year and that the chance of living 3 years was very low. Populations of this skink apparently turn over in about 3 years. Comparative data from Virginia are lacking.

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are brown-back lizard (Hay, 1902), ground lizard (Dunn, 1936), brown-backed skink (Conan t, 1945), and little brown skink (Reed, 1957b).

Conservation and Management: This species is apparently secure in Virginia because of its abundance in some forested habitats and its widespread distribution. Ensuring its survival in any area depends on the availability and size of suitable forested habitat. Maintenance of leaf and humus layers in open forests is required for proper species management. The unanswered question is how large an area is necessary to maintain a viable population that can withstand environmental and natural perturbations. Because this skink plays an important role in community energy dynamics, we need to know more about its population dynamics and its energetic roles as predator and prey.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Amelia

Amherst

Arlington

Bath

Bedford

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Cumberland

Dinwiddie

Fairfax

Franklin

Gloucester

Goochland

Greensville

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Isle of Wight

James City

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Middlesex

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Scott

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Westmoreland

York

CITIES

Chesapeake

Franklin

Fredericksburg

Hampton

Lynchburg

Newport News

Poquoson

Portsmouth

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Verified in 52 counties and 10 cities.

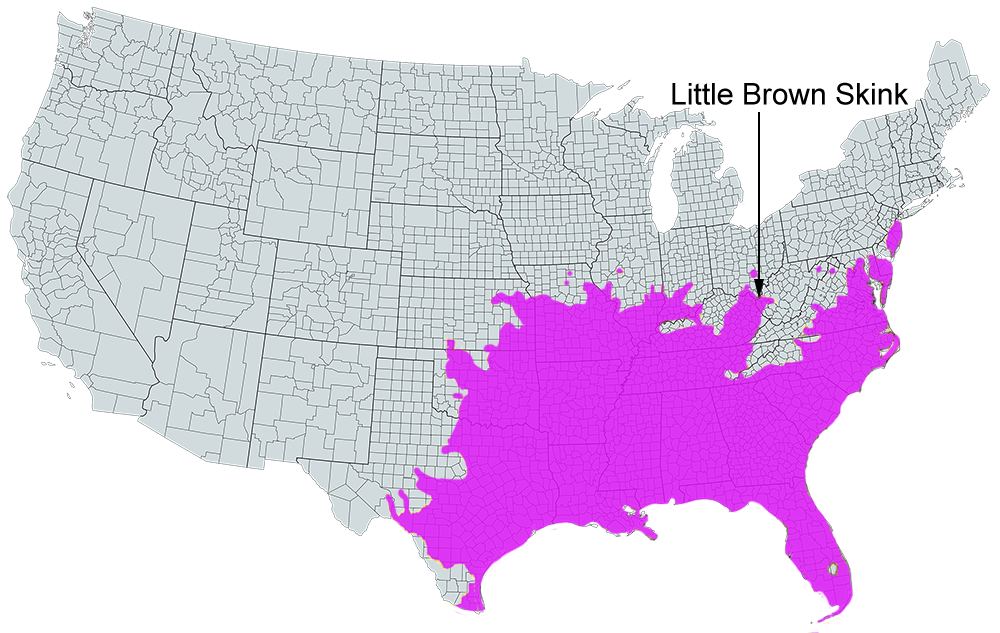

U.S. Range